Internal Deployment of AI Models and Systems in the EU AI Act

Earlier this year, we published the first report of its kind providing a multi-faceted analysis of the risks and governance of internal deployment. We defined ‘internal deployment’ as making an AI model or system available for access and/or usage exclusively within the AI provider that developed it. We also offered reasons as to why autonomous AI Research & Development (AI R&D) is one of the most consequential, and potentially concerning, uses that an AI provider can make of its internal AI models and systems.

Since then, many Chapters of the European Union (EU) Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act have become applicable, including the Chapter regulating general-purpose AI (GPAI) models. The Code of Practice for General-Purpose AI Models has also been released and signed by several AI providers, making the question around the application of the EU AI Act to internally deployed AI models and systems all the more urgent and consequential. At the same time, research and policy interest on the topic of internal deployment has increased across the Atlantic, leading for instance to California Senate Bill 53 requiring “large frontier developer[s]” to “[a]ssess[] and manag[e] catastrophic risk resulting from the internal use of [their] frontier models.”

Today, we build on the work done in our initial report on internal deployment, and specifically we expand on the potential applicability of the EU AI Act to internal AI models and systems. In particular, today we release a new memorandum1 that analyzes and stress-tests arguments in favor and against the inclusion of internal deployment within the scope of the EU AI Act.

In summary, the memorandum:

- Analyzes four interpretative pathways based on Article 2(1)(a)-(c) that could support the application of the EU AI Act to internally deployed AI models and systems.

- Examines three interpretative pathways based on Articles 2(1)(a), 2(6), and 2(8) that could support objections and exceptions to the inclusion of internal deployment within the scope of the EU AI Act, with particular attention to the complexity of the scientific R&D exception under Article 2(6).

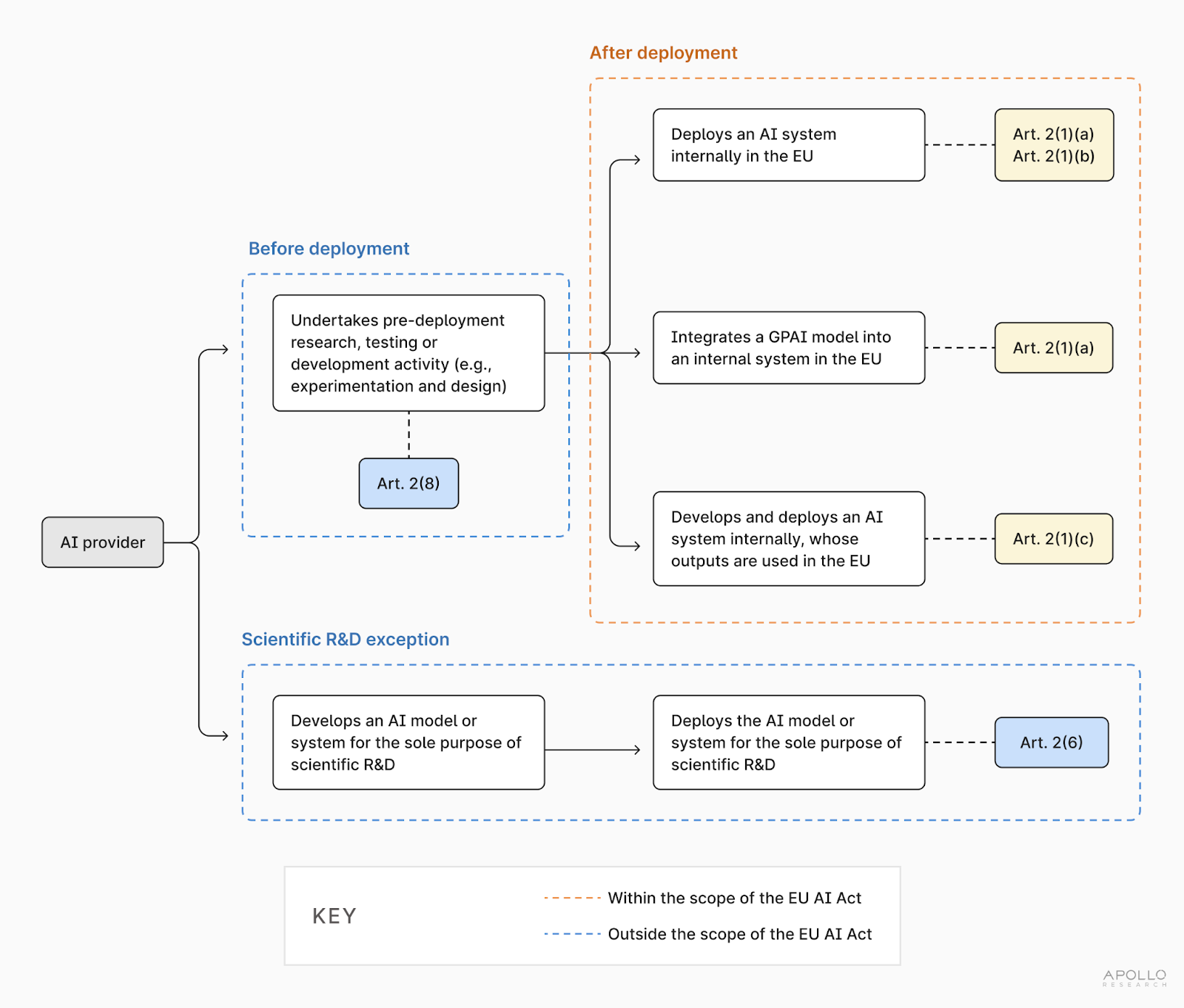

- Finally, illustrates how Articles 2(1), 2(6), and 2(8) can be viewed as complementary to each other, once broken down to their most plausible meaning and interpreted in conjunction with Articles 3(1), 3(3), 3(4), 3(9), 3(10), 3(11), 3(12), 3(63), and Recitals 12, 13, 21, 25, 97, 109, and 110 (see Figure 1).

The following is a brief summary of our analysis. For more nuanced explanations, detailed information, and practical examples, please refer to the full memorandum.

There are several interpretative pathways, under Article 2(1)(a)-(c), supporting the inclusion of internal deployment within the scope of the EU AI Act.

The application of the EU AI Act to internally deployed AI models and systems remains an open question. Compared to other legal frameworks, which mention internal deployment expressly (for instance, California Senate Bill 53), internal AI models and systems are not obviously within the scope of the EU AI Act. However, there are at least four potential interpretations of the EU AI Act that could potentially support the inclusion of internal deployment within the scope of the Act. In summary:

- Article 2(1)(a) (“providers … putting into service AI systems”) could be interpreted to include within the scope of the EU AI Act EU-based or foreign AI developers that make available an internal AI system for their own use in the EU (see §2.1 of the memorandum). This arguably includes internal AI systems that embed GPAI models and are put into service, as clarified by Recital 97 (see §3.1 of the memorandum).

- Article 2(1)(a) (“providers placing on the market … AI systems”) could be interpreted to include within the scope of the EU AI Act EU-based or foreign AI developers that make available an internal AI system for use on the EU market in a business-related context, including for use in the business of the developer itself (see §2.2 of the memorandum).

- Article 2(1)(b) (“deployers of AI systems that have their place of establishment or are located within the Union”) could be interpreted to include within the scope of the EU AI Act EU-based AI developers or EU-based staff of a foreign developer that make use of an internal AI system (see §2.3 of the memorandum).

- Article 2(1)(c) (“output produced by the AI system is used in the Union”) could be interpreted to include foreign AI developers that make available in the EU (e.g., to EU-based staff) the output produced by an internal AI system deployed abroad (see §2.4 of the memorandum).

In other words, a case can be made under Article 2(1)(a)-(c) that the EU AI Act kicks in once an AI system is released, either internally or externally, or once the outputs of an internal AI system are used in the EU.

Article 2(8) seems to confirm this interpretation (see §3.3 of the memorandum). Under Article 2(8), the EU AI Act “does not apply to any research, testing or development activity regarding AI systems or AI models prior to their being placed on the market or put into service.” Article 2(8) concerns the time before any type of deployment, either internal or external, and clarifies that the activities that precede the deployment of an AI model or system (for instance, experimentation and planning) do not trigger per se the application of the EU AI Act.

Some uncertainties remain regarding the internal deployment of general-purpose AI (GPAI) models (see §3.1 of the memorandum). For instance, Article 2(1)(a) (“placing on the market general-purpose AI models”) could be relied on to argue that, since Article 2(1)(a) does not use the expression “putting into service” with direct reference to GPAI models, deploying (i.e., “putting into service”) a GPAI model internally does not trigger the application of the EU AI Act in the same way that deploying (i.e., “putting into service”) an internal AI system does. However, this interpretation does not seem persuasive, for one main reason. At least within frontier AI providers, internal deployment arguably concerns GPAI models that are integrated into AI systems, and given all the necessary affordances and permissions. After system integration, these GPAI models should be considered as “placed on the market” according to Recital 97 and therefore fall within the scope of the EU AI Act under Article 2(1)(a).

There is one exception, under Article 2(6): amongst internal AI models and systems, those that are specifically trained and deployed for the sole purpose of scientific R&D fall outside the scope of the EU AI Act.

Article 2(6) is the main exception to the application of the EU AI Act to internal deployment (see §3.2 of the memorandum). Importantly, Article 2(6) does not exempt internal deployment as a whole, but only selectively carves out from the scope of the EU AI Act “AI systems or AI models, including their output, specifically developed and put into service for the sole purpose of scientific research and development.”

The wording suggests that the exception laid out in Article 2(6) is narrow. This Article only concerns “AI systems or AI models” that an AI provider purposefully develops and deploys for one exclusive purpose: scientific R&D. In other words, to fall within the exception set forth by Article 2(6), the only purpose of both training and deploying an internal AI model or system must be scientific R&D.

The EU AI Act does not define scientific R&D. However, its meaning could be inferred from: (1) the EU AI Act’s juxtaposition of scientific R&D to “product-oriented” R&D (which, by contrast, falls within the scope of the EU AI Act; see Recital 25); and (2) the definition that other EU legal frameworks provide of scientific R&D and product-oriented R&D. For instance, helpful points of reference are Regulation (EC) 1907/2006 of December 18, 2006 (REACH Regulation) and the relevant Guidance by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). The REACH Regulation and ECHA’s guidance provide an indication of the scale (i.e., under controlled conditions, and at a laboratory scale such as in vitro) and the purpose (i.e., experimentation, analysis, monitoring and diagnostics that are not aimed at product development or the further development of a product)of scientific R&D, compared to product-oriented R&D.

While the European Commission may decide to interpret scientific R&D differently (for instance, to include AI R&D that is truly grand scale, e.g. of a scale comparable to the Large Hadron Collider at the CERN, or the Human Brain Project), the points of reference given by the REACH Regulation and ECHA’s Guidance could help the European Commission identify some initial examples that could fit the definition of scientific R&D, such as ‘model organisms,’ AI models or systems developed for mechanistic interpretability, AI models or systems used for purely for scientific experimentation (e.g., to simulate how a fruit fly walks, flies and behaves).

Articles 2(1), 2(6), and 2(8) are, in fact, complementary to each other.

Rather than being conflicting, Articles 2(1), 2(6), and 2(8)––interpreted in conjunction with Articles 3(1), 3(3), 3(4), 3(9), 3(10), 3(11), 3(12), 3(63), and Recitals 12, 13, 21, 25, 97, 109, and 110––are, in fact, complementary to each other (see Figure 1; §4 of the memorandum). Specifically:

- The deployment of an AI model or system, either within or outside an AI provider, triggers the application of the EU AI Act. This is clarified by Article 2(1)(a)-(c), which sets the clear-cut rule that making available or using an AI system or its outputs in the EU triggers the application of the EU AI Act, and, in doing so, does not differentiate between internal systems and external systems.

- GPAI models trigger the application of the EU AI Act once they are integrated into an AI system (whether internal or external) that is put into service, or once they are independently placed on the market. This is clarified by Article 2(1)(a) and Recital 97, according to which a GPAI model counts as being placed on the market once it is integrated into an AI system. System integration is necessary or at least beneficial for most of the possible internal uses of a GPAI model, which in turn narrows down the number of cases in which an internal GPAI model is not covered by the EU AI Act.

- Internal AI models or systems specifically developed and deployed for the exclusive use of scientific research and development fall outside of the scope of the EU AI Act. This exception is laid out in Article 2(6). Its scope is narrow. While the EU AI Act does not define “scientific research and development” it is possible to infer from Recital 25 and the REACH Regulation that scientific R&D is different from “product-oriented” R&D. By contrast to purely scientific R&D, any AI model or system that engages in R&D that is product-oriented does not fall within the Article 2(6) exception.

- Research and development activities that AI providers undertake before “putting into service” or “placing on the market” an AI model or system (i.e., before internal deployment) do not trigger per se the application of the EU AI Act. This is clarified by Article 2(8), according to which “any research, testing or development activity regarding AI systems or AI models prior to their being placed on the market or put into service.” The precise scope of the exempted “research, testing or development activity” remains to be defined (e.g., experimentation and design, pre-training, post-training).

Read the full memorandum here and our report on the risks and governance of internal deployment here. Please contact us if you are interested in learning more.

- Written for the Cambridge Commentary on EU General-Purpose AI Law (not reviewed yet).

↩︎