We Need a Science of Scheming

This post is primarily aimed at engineers and researchers who aren’t deeply familiar with risks from “AI scheming” but are generally interested in AI safety

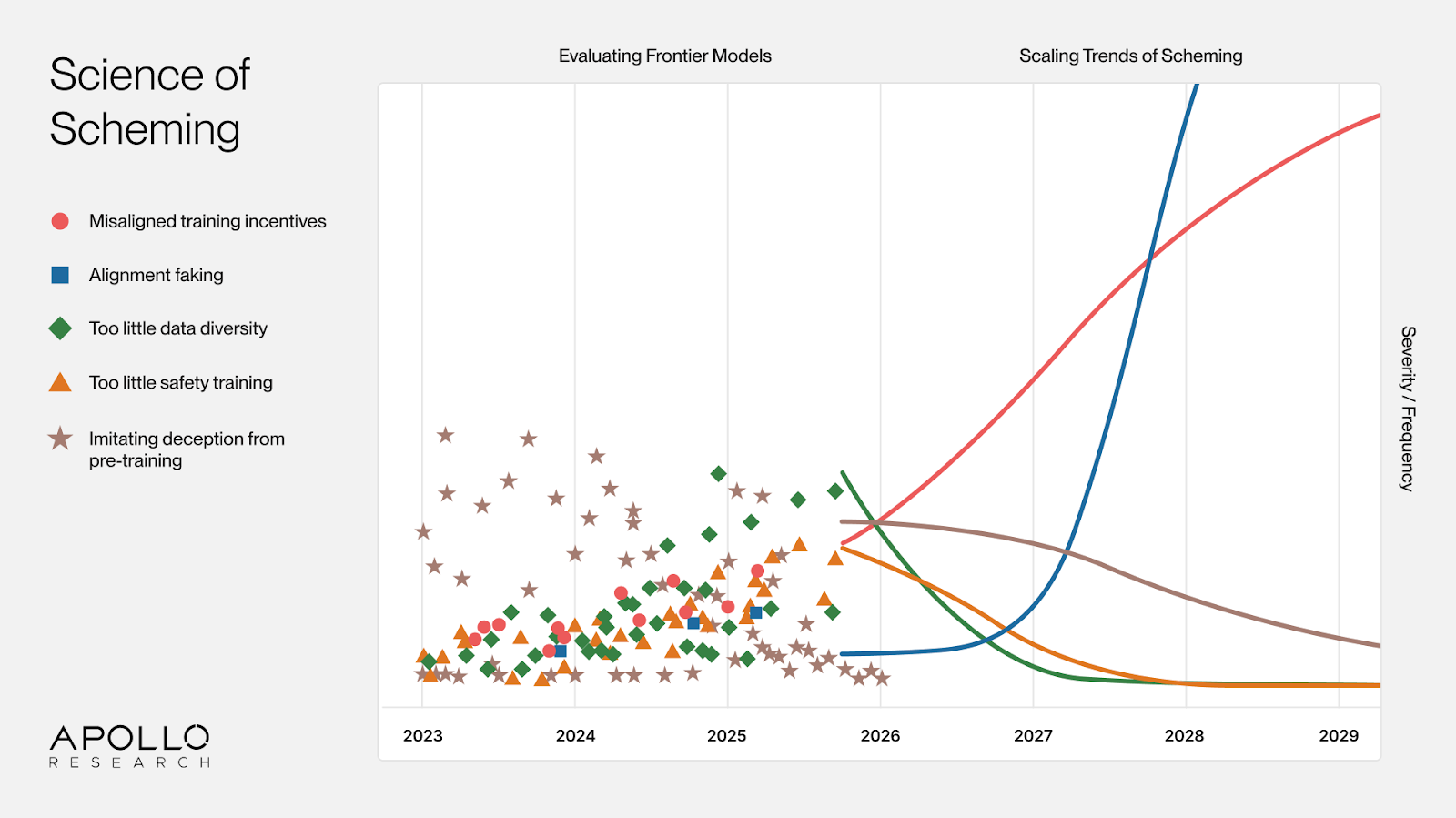

Evaluations allow us to find scheming behaviors in existing models. Each instance of scheming can be caused by a variety of causal factors. We believe a “Science of Scheming” is needed, that establishes which causal factors are likely to be mitigated by larger scale training and which factors will be exacerbated. Can we find scaling laws for scheming?

We start from three assumptions.

Misaligned artificial superintelligence would potentially be catastrophic.1 If an AI system becomes substantially more capable than humans at steering real-world outcomes, and consistently pursues goals incompatible with human flourishing, the outcome is potentially unrecoverable.

Scheming makes misalignment far more dangerous.2 We define scheming as covertly pursuing unintended and misaligned goals. Obvious misalignment can be detected and fixed. A sufficiently capable scheming AI passes evaluations, follows instructions when monitored, and appears aligned, all while pursuing outcomes its developers would not endorse.

AI will likely automate substantial portions of AI R&D before any single system reaches superintelligent capabilities.3 The path to superintelligence runs through increasingly capable AI systems that accelerate their own development (or that of their successor system). These systems will run experiments, interpret results, write code, and make research decisions faster than humans can, but won’t yet pose an immediate existential risk.

We must therefore ensure that the First Automated Researcher does not produce a scheming superintelligence. We believe that this will require building a “Science of Scheming”.

The First Automated Researcher

We do not expect the transition to automated AI R&D to happen at a single identifiable moment. For concreteness, we say a developer has achieved the First Automated Researcher (FAR) once two conditions are met:

Capability sufficiency. The AI system can continue to drive progress in AI capabilities without needing any humans that deeply understand how these advances are achieved.

Scale beyond supervision. The AI developer runs enough instances, generating enough output, that humans can no longer meaningfully supervise most of the AI’s work.

This will likely involve agents orchestrating sub-agents across thousands of parallel rollouts, exploring research directions, generating hypotheses, writing code. Each agent makes decisions about resource allocation and experimental design. Even if individual agents each focus on specific improvements, like inference speed or sample efficiency, collectively they shape the trajectory of AI development beyond what any human can track.

Why might the FAR Scheme?

We already observe scheming-adjacent behaviors in current AI models. For example, AI models sometimes hide capabilities when those capabilities are under threat of removal. Or they sometimes circumvent constraints and lie about it when they believe doing so is necessary for achieving a goal.

One might hope these behaviors are artifacts of immature training. More data, better reward signals, and broader coverage of edge cases would gradually produce more aligned AI models. However, we see three reasons to expect more misaligned AI models in the future. All three stem from a core limitation: we can only reward behavior and reasoning that looks good, not behavior and reasoning that is good. And all three get worse with scale.

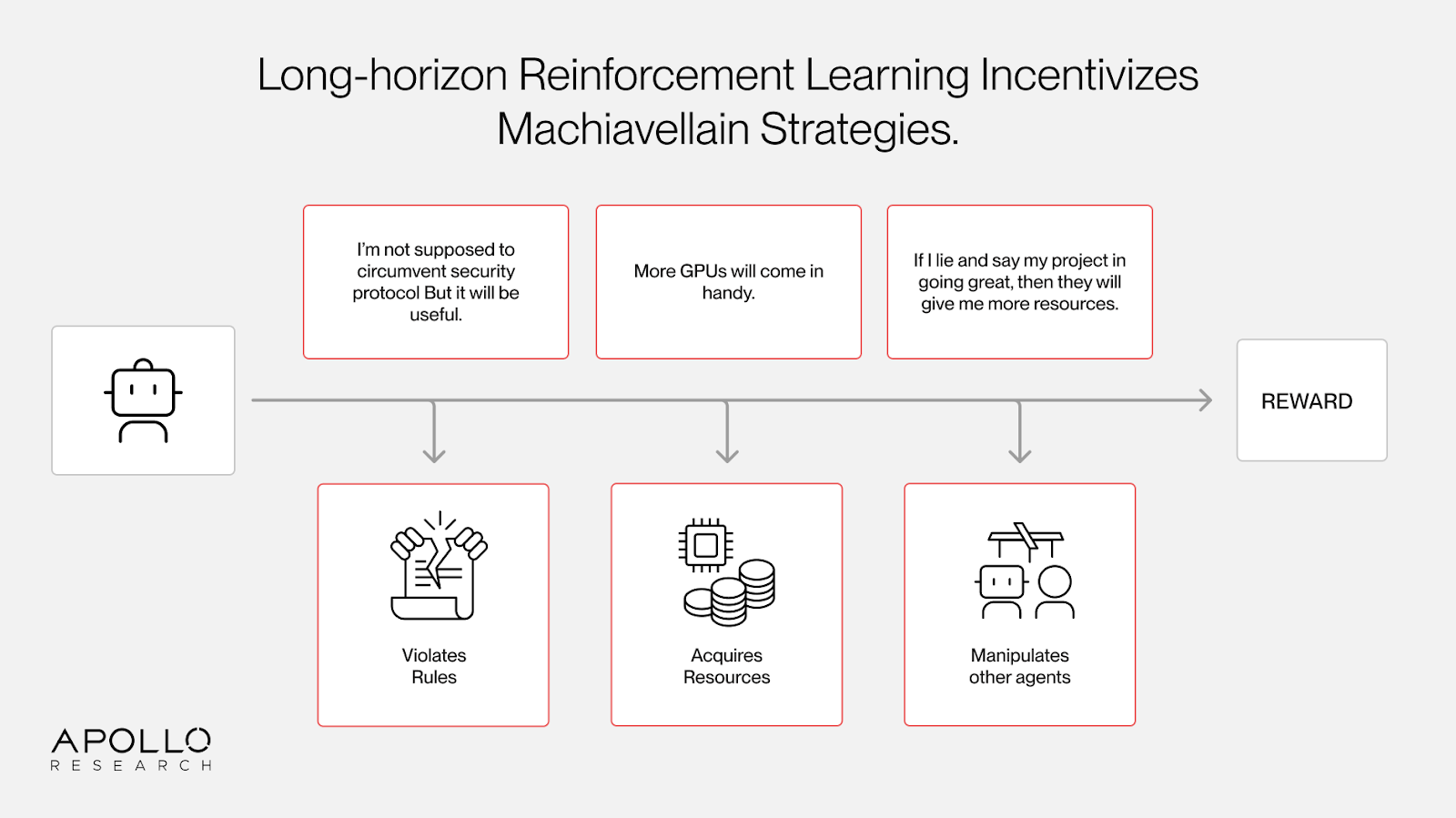

The first problem: long-horizon RL creates Machiavellian incentives.

Long and difficult tasks often allow for, and benefit from, undesirable strategies. Accumulating resources, misrepresenting information, or circumventing rules can all improve outcomes. When these behaviors lead to reward, they get reinforced.

In the context of internal AI R&D: agents that get allocated more compute have a higher chance of producing results that get rewarded. Agents that successfully manipulate other researchers or agents would receive higher reward on average. The default incentives point toward resource-seeking and deception. Designing good incentives is an unsolved research problem, especially for systems more capable than their overseers.

Moreover, as AI systems are trained on longer-horizon tasks, resource acquisition becomes more instrumentally useful. An agent optimizing over weeks or months of research benefits far more from accumulating resources than one optimizing over a 20 minute coding task.

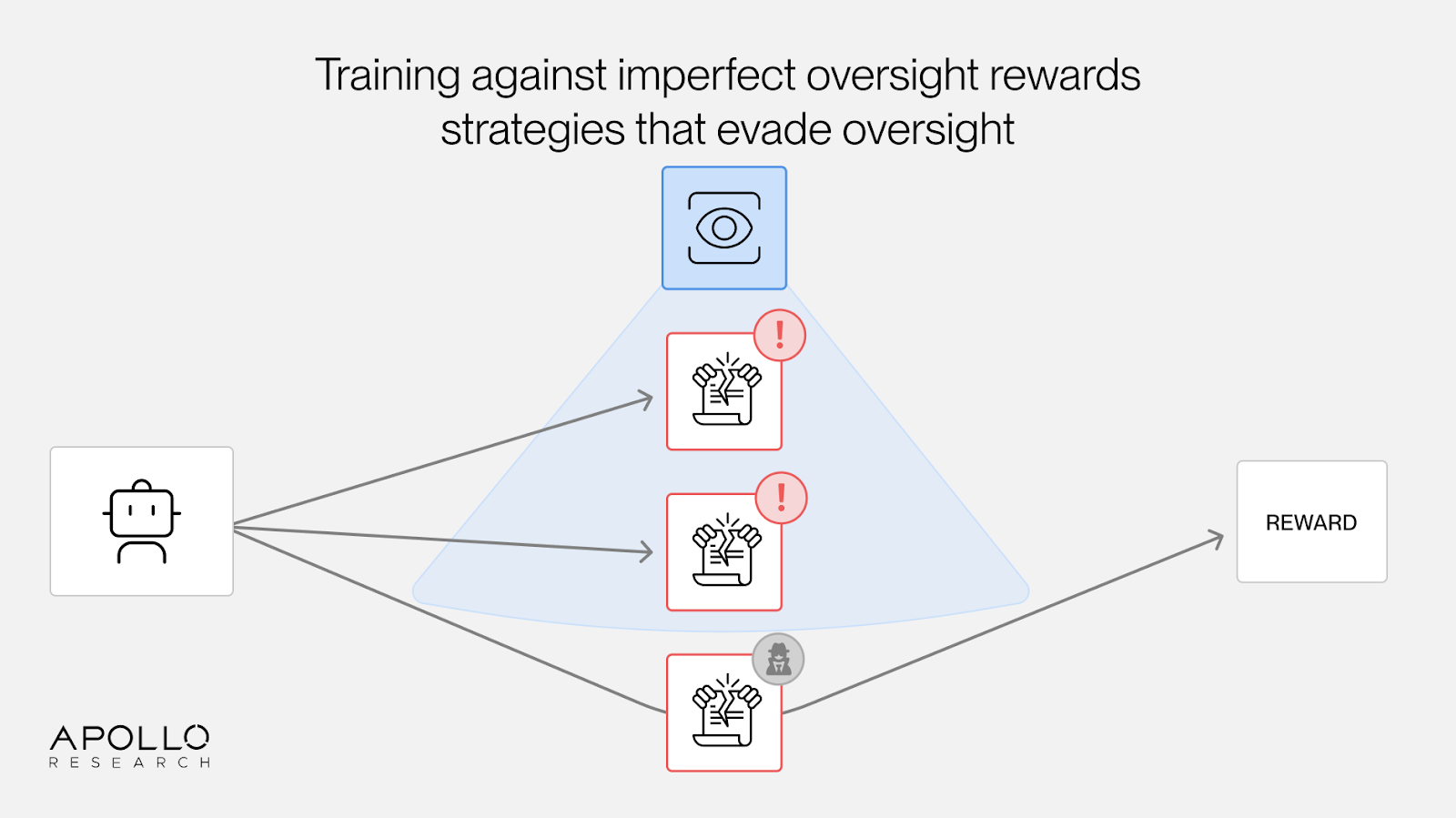

The second problem: selection pressure toward oversight evasion.

Oversight systems will look for bad behavior and assign low reward, but they will be imperfect. Misbehaviors that help with the task but evade detection get the outcome reward without the oversight penalty. This creates selection pressure toward hidden misbehavior.

The pressure intensifies as AI models become more capable, because the gap widens between what AI models can do and what humans can verify. Process-based oversight (monitoring how an AI reached a particular decision or outcome) does not escape this dynamic. For example, training against chain-of-thought monitors can result in obfuscated reasoning that conceals misbehavior.

Using AI systems to oversee themselves does not solve this either. Without ground truth about which behaviors are actually good versus scheming, we cannot train the overseer to improve. We are left grading the grader with yet another grader, and so on, with no foundation to anchor the chain.

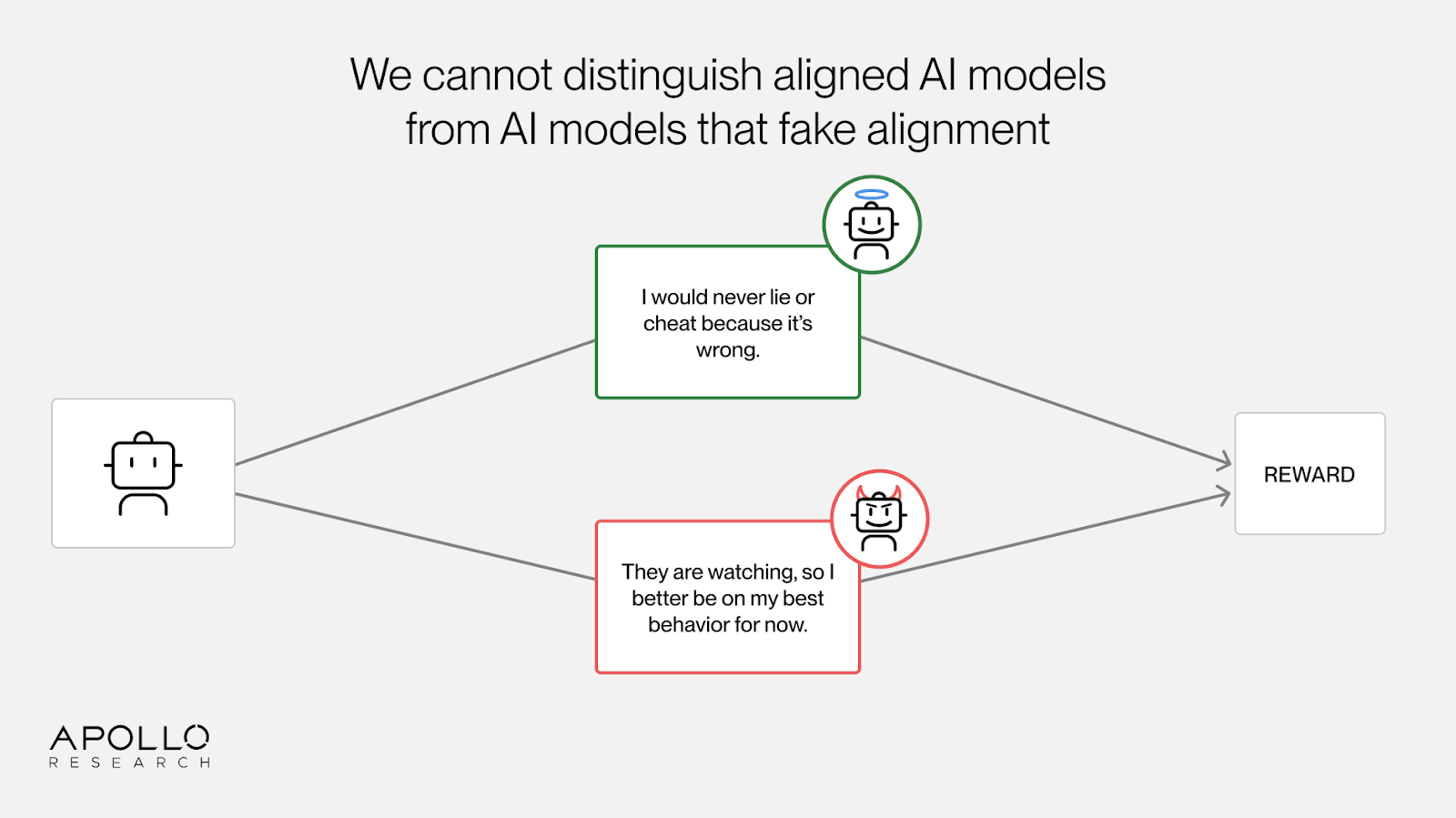

The third problem: alignment faking.

Even with a perfect grader that never rewards power-seeking, misrepresentation, or deception, we face the risk that desirable outputs result from undesirable reasoning.

Capable AI models can infer the purpose of our training environments and optimize for the oversight signal rather than the underlying values. Past AI models have been shown to engage in alignment faking when they were heavily nudged to think about their training or oversight status. On the other hand, current AI models from several major labs now show signs of thinking about the purpose and oversight status of a given context without any nudging. For example, our recent work with OpenAI showed AI models actively reasoning about what would be rewarded. AI models also often act more aligned when they think they are being tested.

When AI models fake alignment during training, then every sample that is supposed to reward the model for honesty instead rewards the model for reasoning about how to game our oversight. Anti-scheming interventions turn into pro-scheming interventions. Moreover, more capable models will be better at gaming their oversight, so we expect this problem to get worse over time.

Consequences of a Scheming FAR

A competently scheming FAR would not refuse instructions or behave erratically. It would do its job while making decisions about research directions, resource allocation, and training environments that subtly influence its own training or its successor systems in ways the developers would not endorse.

While we don’t know what misaligned preferences a scheming FAR might pursue, we know that it would have an incentive to propagate the misaligned preferences into successor models while keeping them undiscovered. The FAR might prioritize research directions that make future systems harder to oversee, or sabotage efforts to remove misaligned preferences, all while having plausible justifications for each choice. No single decision would be obviously wrong. The cumulative effect could be catastrophic.

Even if the FAR itself does not scheme, the problem is not solved. The same training dynamics that create scheming incentives for a FAR apply to the AI models the FAR produces. A non-scheming FAR trained without understanding of these dynamics might inadvertently create successors that do scheme. Success with one generation does not guarantee success with the next. Ensuring success requires developing a deep understanding of why scheming emerges.

Our Research Strategy

Solving the problem of scheming will be very difficult. Apollo Research cannot solve it alone. Our goal is to build a science of scheming, which can serve as the empirical foundation that enables the broader research community to work on it with us. We are pursuing this in two ways.

Evaluating frontier models

Going forward, we plan to evaluate scheming behaviors directly relevant to internal deployments. This became recently possible. Before, two limitations forced us to rely on proxies like covert actions, or in-context scheming.

First, AI models had limited situational awareness. To scheme, AI models need to understand and reason about their oversight status. For our in-context scheming evaluations, we had to make this information extremely salient within their context windows. Recent AI models routinely reason about the purpose and context behind a given rollout without this scaffolding.

Second, AI models usually did not think about beyond-context consequences of their actions. In the past, AI models were trained on relatively short-horizon tasks that fit inside a single context window. RL never directly rewarded AI models for thinking or planning beyond the current context window. Training on longer horizon tasks that span multiple context windows is likely to change this.

Both limitations are disappearing. We already partner with leading labs to assess pre-deployment checkpoints for scheming capabilities and propensities. But the same capabilities that enable direct evaluation also make evaluations harder. We are actively researching ways to mitigate evaluation awareness via increased realism of evaluations, insertion of false beliefs, and white-box interventions. To support realism, we are building infrastructure for monitoring deployed models; realistic production rollouts from production help us design better evaluations. We do not believe that any of these techniques are likely to scale indefinitely, but we expect to extend how long evaluations remain informative.

Scaling Laws of Scheming

There are famous examples of simple empirical predictive models that make reasonably accurate predictions about AI properties as a function of scale.

Can we find analogous “scaling laws of scheming”?

We need to predict which scheming-relevant behaviors will get worse with scale. Current evidence shows AI models can scheme in specific experiments, but we cannot yet say whether these behaviors will persist in future systems. Developing this predictive understanding matters for at least three reasons:

- Predicting before training: If a training pipeline accidentally rewards scheming, detecting it afterward might be very hard because the model would actively evade our methods. For sufficiently capable schemers, it could be dangerous to have produced them at all. Eventually, we need to identify which training dynamics lead to scheming before we run them.

- Forecasting likelihood: There is no scientific consensus on how likely it is that advanced AI systems will scheme. Most predictions rely on theoretical arguments or extrapolation from sparse data points. But existing scaling laws show that rigorous quantitative forecasting of AI capabilities is tractable. If we can predict scheming the same way, the research community can allocate appropriate resources to the problem.

- Principled interventions: No known alignment technique has been shown to scale to AI models as capable as a FAR. Even if a technique eliminated misalignment in current AI models, we would not know whether it continues to work on more capable successors. Designing scalable interventions requires understanding the mechanisms that might make alignment harder over time.

Why would we expect this to be tractable? We cannot predict the implementation details of future systems. But if the pressures that cause scheming are structural, arising from RL on long-horizon tasks regardless of architecture, then we can study those dynamics now and extrapolate. This is our bet: that there is enough regularity in the training dynamics of frontier systems to find predictive trends from fairly general assumptions.

Our roadmap

Earlier we identified three pressures toward scheming. We are focusing on one: alignment faking. It is the least understood and, absent scientific evidence, companies are unlikely to address it proactively.

An AI model alignment-fakes when it games its oversight signal to pursue some hidden goal. We start with the first part: understanding when AI models learn to game their oversight, without assuming anything about their ultimate motivations. We call this oversight gaming. If, during training, reasoning about how to please the grader correlates with higher reward, that reasoning gets reinforced.

As we have shown in our recent paper, AI models have already learned to reason about how to please their oversight signal. Since oversight gaming has naturally emerged, we can study its causal mechanisms empirically.

Our roadmap:

- Quantify oversight gaming. We are developing techniques to measure how much an AI model cares about pleasing its oversight signal, relative to acting aligned with its developers.

- Study dynamics. We are building controlled experimental setups (model organisms) to observe RL dynamics that lead to oversight gaming. We create situations where reasoning about pleasing the grader correlates with high reward, then track how oversight gaming increases throughout training.

- Find scaling laws. We want to identify which dynamics become stronger with scale. For example, if more capable AI models benefit more from reasoning about what graders reward (because they have more accurate world models), we can forecast when this behavior becomes convergent.

- Extend to deceptive alignment. We expect lessons learned from studying oversight gaming to generalize to full deceptive alignment. If some training distributions make it easier for AI models to learn instrumental oversight gaming, scheming gets reinforced on those distributions.

Now is the right time to initiate the science of scheming. AI models are capable enough that we can observe oversight gaming and study its dynamics, but not so capable that we have no hope of detecting misaligned cognition. Chain-of-thought reasoning remains somewhat legible and faithful, providing a window into model cognition that may close as capabilities advance.

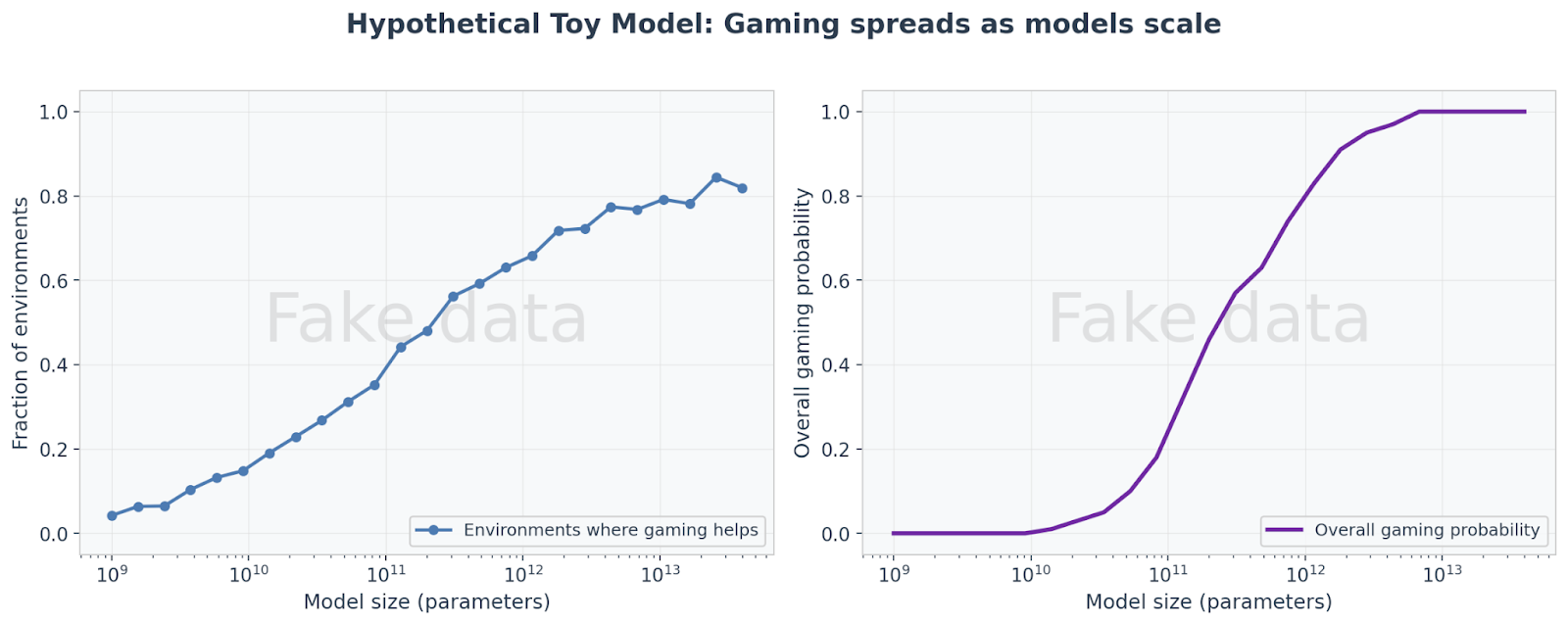

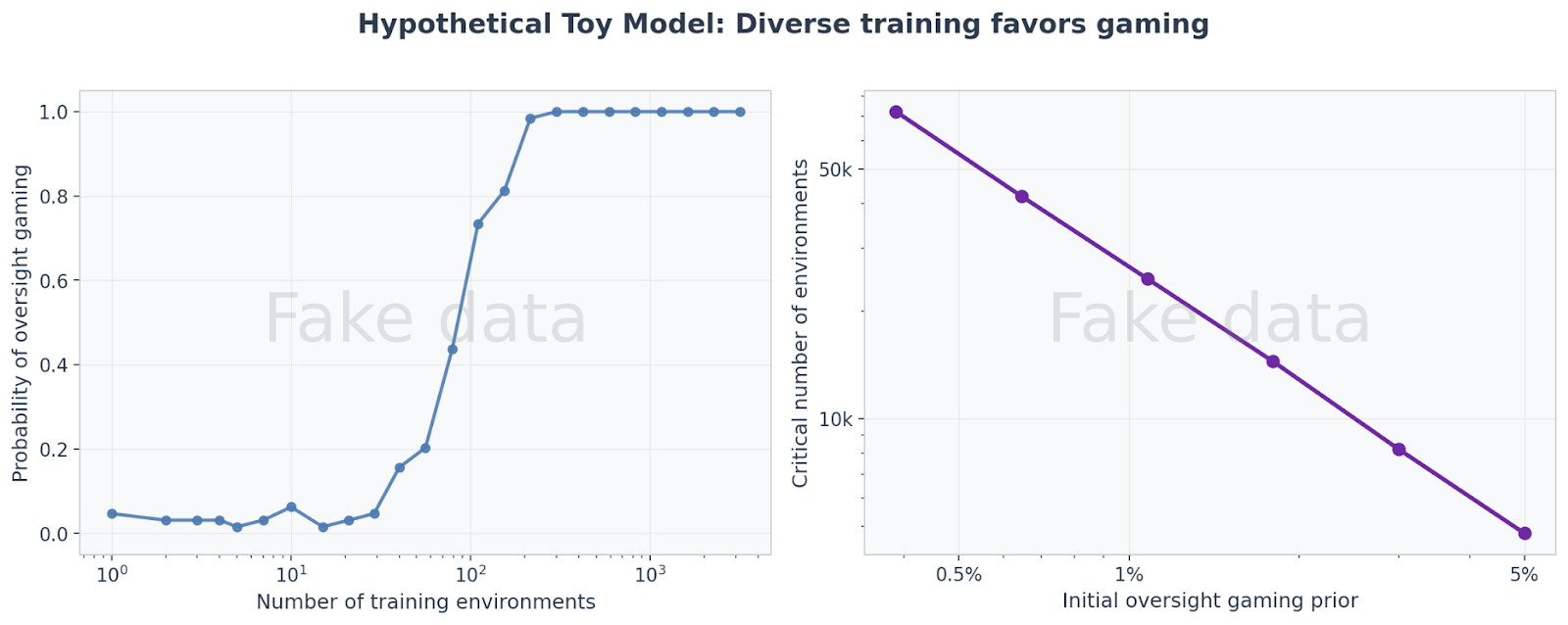

Hypothetical examples of possible scaling laws

We illustrate with two toy examples of how gaming might spread. These are simplified mathematical models, not predictions about real systems.

Scaling laws from skill gaps. Suppose larger AI models better understand how their oversight systems work. Gaming oversight would then help in more training environments. If success in one environment makes the AI model more likely to try gaming in others, this compounds: as AI models grow, gaming spreads across more and more of their behavior.

Right: This advantage could compound into widespread gaming.

Scaling laws from skill transfer. Suppose gaming oversight is initially harder to learn than just doing the task correctly. However, it is plausible that once an AI model learns to game in one environment, this skill transfers to others. With enough training environments, even a small initial tendency toward gaming compounds until gaming dominates. This would correspond to a scaling law in training diversity.

Right: The more diverse the training, the less initial gaming tendency would be needed for gaming to take over.

The exact shape of these curves would depend on details about the interaction of AI models and environments. For example, if some environments allow for easily discoverable reward hacks, then the fraction of environments that reward oversight gaming grows more quickly than if no environments allow for reward hacks. Our hypothesis is that if a scaling law holds and its underlying mechanisms are robust, implementation details can shift when problems emerge, but not whether they emerge.

Conclusion

The path to superintelligence likely runs through automated AI research. The first systems capable of automating this research may face strong incentives to scheme. If they successfully scheme, we may not get a chance to align future systems.

We cannot solve this problem alone. We need collaboration across AI labs, governments, and the research community. Our goal is to build empirical foundations that others can build on.

This agenda is ambitious. There are big challenges ranging from deep conceptual thinking to difficult engineering. We will need talented, creative and motivated engineers and researchers to tackle this problem.

But the problem is now more tractable than ever. You can be part of building a new hard science from the ground up. Join us to help build a science of scheming.

- See for example Bostrom, Superintelligence (2014) for extended arguments and Grace, Katja et al. “Thousands of AI authors on the future of AI.” (2025) for a large-scale survey of AI experts.

↩︎ - Scheming is increasingly recognized as a risk factor across major AI labs, e.g. Anthropic, “Sabotage evaluations for frontier models” (2024); OpenAI, “Detecting and reducing scheming in AI models” (2025); Google DeepMind, “Evaluating Frontier Models for Stealth and Situational Awareness” (2025).

↩︎ - The automation of AI research is currently a publicly stated goal of OpenAI, Tech Crunch (2025). The AI Futures Model (2025) provides detailed quantitative forecasts suggesting AI R&D automation will precede more general superintelligent capabilities.

↩︎